Jane Waller

Jane Waller is one of those people the British find difficult to categorize: someone who excels in a whole range of activities. After studying drawing, painting and sculpture she turned to ceramics, producing work described by the Arts Editor of the International Herald Tribune as “among the greatest creations of twentieth century pottery”.

And as if that isn’t enough, she is a professional writer – with 18 published books on a range of subjects. Her first book, ‘A Stitch in Time’ volume one, helped to launch a revival of interest in hand knitting. Since then, in addition to fashion, she has written children’s fiction, social history and three acclaimed books on ceramics.

Jane was born in the Chiltern Hills, in Buckinghamshire, a wooded area 40 miles north-west of London and this is where she now lives – in a flint and brick cottage on the edge of a wood – with her husband, Michael Vaughan-Rees, a writer and language specialist.

For many years they lived right in the center of London, in Waterloo, where they were active in campaigning to prevent the area becoming overrun by office blocks. Jane notably launched the successful Save the Oxo Tower Campaign, to guarantee the future of one of the few outstanding art deco buildings in the London area.

Jane’s mother was a distinguished stained glass artist, her father a surveyor and architect, specializing in the restoration of old buildings. They bought a Georgian manor house in Aylesbury, and the whole family set about restoring it. (Jane’s diaries for the period typically refer to ‘mixing two hundredweight of cement for Daddy’).

All five Waller children emerged from this background with artistic temperaments: Edmund is a landscape architect, Lynda a stained glass artist, Vanessa a potter, and Geoffrey specialises in providing the lighting for major architectural and artistic projects in New Zealand.

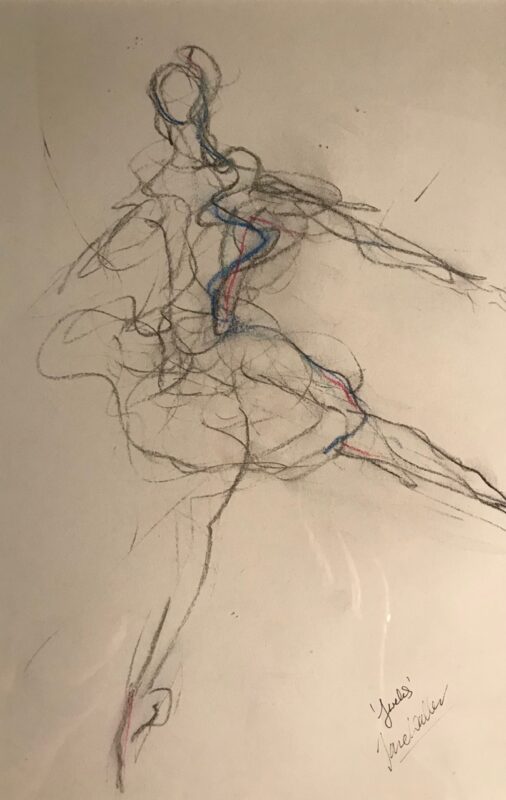

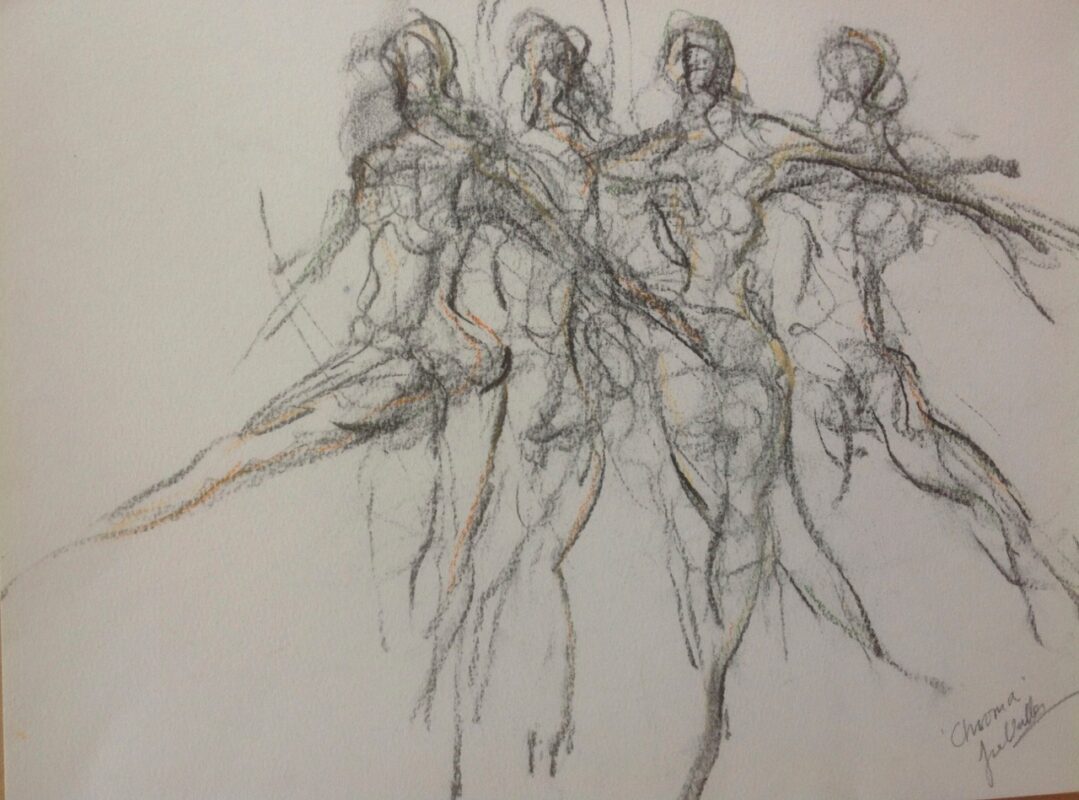

When Tony Birks died a few years ago, I no longer drew the Butoh Dancers; but a wonderful surprise awaited me: I can now draw in the dark at ‘Ballet Dress Rehearsals’. The orchestra strikes up, the curtains open … and the auditorium lights go out. So I home in on the stage, and draw just the movement the dancers make. I’m not looking at the paper at all when I draw, but I use my whole arm, and draw freely. I found, quickly, that the orchestral music gives a kind of ‘Signature’ to each particular ballet. When the lights come on again, I see what I have drawn … or not. Sometimes, later, I add – very quickly – touches of colour; but I do not ‘work’ on the drawings, as that stops them moving. In the end, what I want is for people who buy my work to have a picture on their wall, which, when they walk past, does a little jiggle for them – so they are not ‘static’ pictures.”